Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información.

Año. Vol. 29, 1-21

ISSN 2695-5016

REACTION AND DENIAL PROPAGANDA ON SOCIAL MEDIA: THE ANDALUSIAN PARTIES ON YOUTUBE

PROPAGANDA DE REACCIÓN Y DE NEGACIÓN EN REDES SOCIALES: LOS PARTIDOS ANDALUCES EN YOUTUBE

Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla[1]. Universidad de Sevilla. Spain.

María del Mar Rubio-Hernández. Universidad de Sevilla. Spain.

Jorge David Fernández Gómez. Universidad de Sevilla. Spain.

Julieti Sussi de Oliveira. Universidad de Sevilla. Spain.

Financing. This paper originates in the research project proposal PRY095/19, funded by Fundación Pública Andaluza Centro de Estudios Andaluces, 11th edition. The research project title is “Communication, Participation, and Dialogue with the Citizenry in the ‘New Politics’ Age: The Use of Social Media by Andalusian Political Parties”.

How to cite this article:

Hernández-Santaolalla, Víctor; Rubio-Hernández, María del Mar; Fernández Gómez, Jorge David, & de Oliveira, Julieti Sussi (2024). Reaction and denial propaganda on social media: the andalusian parties on YouTube [Propaganda de reacción y de negación en redes sociales: los partidos andaluces en YouTube]. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información, 29, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.35742/rcci.2024.29.e296

ABSTRACT

Introduction: For political organizations, social networks, far from being a space for dialogue, have become another tool for one-way communication. Thus, this article aims to delve into the propagandistic use of YouTube by political parties, focusing on Andalusia, the Spanish region with the largest population and the first in which the extreme right-wing party Vox achieved an influential parliamentary representation. Methodology: A content analysis was applied to 999 videos published throughout 2020 by political parties with parliamentary representation, taking into account variables such as the presence of party symbols, the type of propaganda used and the reference to a rival political party. Results: Among the results, the difference in the use of denial propaganda by parties located on the right of the ideological spectrum and reaction propaganda by parties located on the left stands out. Discussion: In view of the above, the results are discussed in terms of de-ideologization, populism and reduction of programmatic ideas. Conclusions: In the end we find that there are differences in terms of the type of propaganda used (highlighting reaction and denial) pointing to a notable inability of the parties to raise alternatives which is related to the rise of populism and the pseudo-abandonment of ideology.

Keywords:

Propaganda; far-right; populism; Andalusia; de-ideologization; YouTube.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Para las organizaciones políticas, las redes sociales, lejos de ser un espacio de diálogo, se han convertido en una herramienta más de comunicación unidireccional. Así, este artículo tiene como objetivo profundizar en el uso propagandístico de YouTube por parte de los partidos políticos, centrándose en Andalucía, la región española con mayor población y la primera en la que el partido de extrema derecha Vox logró una representación parlamentaria influyente. Metodología: Se aplicó un análisis de contenido a 999 videos publicados a lo largo de 2020 por los partidos políticos con representación parlamentaria, teniendo en cuenta variables como la presencia de los símbolos del partido, el tipo de propaganda utilizado y la referencia a un partido político rival. Resultados: Entre los resultados, destaca la diferencia en el uso de la propaganda de negación por parte de los partidos ubicados a la derecha del espectro ideológico y de reacción por parte de los partidos ubicados a la izquierda. Discusión: Visto lo anterior, los resultados se discuten en términos de desideologización, populismo y reducción de ideas programáticas. Conclusiones: Al final encontramos que hay diferencias en cuanto al tipo de propaganda que se utiliza (destacando la de reacción y la de negación) apuntándose una notable incapacidad de los partidos para plantear alternativas que se relaciona con el auge del populismo y el pseudoabandono de la ideología.

Palabras clave:

Propaganda; extrema derecha; populismo; Andalucía; desideologización; YouTube.

1. INTRODUCTION

The advent of the social media in the communication ecosystem, was seen as an opportunity for achieving full democracy, for it enabled citizens to communicate directly with political leaders (Pedersen and Rahat, 2019). Conversely, there is currently a prevalence of one-way communication and propaganda, although senders now have new dissemination channels at their disposal (Ramos-Serrano et al., 2018). From Obama to Trump, Bolsonaro or Bukele, politicians have encountered an interesting vehicle in social media for disseminating their manifestos. This does not mean that network communication has not brought about changes in the practice and study of propaganda (Chaudhari and Pawar, 2021), for new concepts like that of “computational propaganda” have even been coined (Woolley and Howard, 2019).

The growing abandonment of ideology on the part of political parties together with the electorate’s lack of party loyalty, explain why the Internet and social media are interesting for and relevant to propaganda. On the one hand, because this alleged abandonment of ideology has prompted mainstream parties to offer the citizenry increasingly more simple messages, based on entertainment and personal stories, in a process of individualization and privatization (Castells, 2009; Maarek, 2011; McGregor et al., 2017). On the other, because unlike the mass media whose messages have a narrower ideological spectrum (Chomsky and Herman, 1988), the Internet would cater to a broader one, including proposals ranging from the extreme left to the extreme right. In the United States, cases like those of Ron Paul, the Tea Party and Bernie Sanders, or those of Podemos and Vox in Spain, give a good account of how approaches that are presumptively far removed from the dominant ideological spectrum have successfully carved out a political niche for themselves thanks to the use of the Internet. With respect to Spain, the participation of Podemos in the 2014 European elections marked a change in the political context. So, both this party and Ciudadanos (Cs) would champion the concept of “new politics”, transforming the two-party system into a multiparty one; a new structure that facilitated the incorporation of new organizations putting forward different ideological proposals by extending the spectrum at both extremes.

This has been the case of Vox, which has gained a strong foothold in the Andalusian parliament after winning twelve seats in the 2018 regional elections and 14 in 2022. One of the most interesting aspects of Vox, however, is its management of social networking sites (SNSs), especially those that have a less apparent political slant and are aimed at a younger audience, such as TikTok (Cid, 2020; Simón, 2020), generating, along with Podemos, a greater commitment and exploiting more effectively the specific possibilities of the platform (Cervi and Marín Lladó, 2021).

In the wider context of playful politics (Vijay and Gekker, 2021), it is the Spanish political parties that are apparently further removed from the centre of the ideological spectrum that have understood how the platform currently works, not so much exploiting their official channels as ensuring that users, or netroots (Armstrong and Moulitsas, 2006), consolidate their own discourse.

Against this backdrop, the aim here is to delve deeper into the use that political parties put social media, specifically YouTube, for propaganda purposes, focusing the case study on Andalusia, a region of southern Spain which became, as already noted, the first autonomous community in which the radical right-wing party Vox won a substantial number of seats in Parliament.

1.1. Political propaganda and YouTube

YouTube is one of the most popular social media. This platform revolves around videos, a format to which it chiefly owes its success when engaging diverse types of voters. It is one of the platforms to which political parties resort most during election campaigns. Indeed, the considerable amount of research on the political implications of YouTube evinces the growing importance that scholars now attach to it as a political communication and propaganda tool. Not without reason, Davis et al. (2009) highlighted how it had already become a popular platform for posting videos on politics, although, in this respect, Twitter—apart from Facebook—is the SNS that has attracted most attention owing to the opportunities that it offers for political debate. With over two billion users registered monthly and more than five hundred hours of content generated every minute, YouTube (2022) is currently the most popular video platform with the greatest global impact. Considering these figures, the advantages that its offers for content creation and the fact that a higher proportion of their voters use the platform, it should come as no surprise that political parties and representatives have turned to it. Similarly, the media, as with users in their facet of political prosumers, employ this channel, for “the structure of YouTube encourages the growth of political ecosystems” (Munger and Phillips, 2020, p. 196). In any event, users pay less attention —and in a different way— to political videos than to the entertainment kind (Möller et al., 2019).

The scientific literature approaching YouTube from this perspective focuses on diverse aspects relating to the communication process. On the one hand, the accent is placed on the profile of political parties and representatives as senders in the digital environment, with the prevalence of a one-way use of the platform and no interaction whatsoever with users (Balci and Saritaş, 2022). On the other, enquiries have been made into user response, characterized by an abundance of hostile and sexist messages (Lima-Lopes, 2022). Likewise, Fischer et al. (2022) have studied the theme and nature of content, identifying typologies like “partisan mockery” and “engaging education” in the analysed videos, while Finlayson (2020) has highlighted the predominance of a populist style, a political performance style typical of digital media.

Although there are also studies of the use of YouTube in the European political context (Litvinenko, 2021; Pineda et al., 2019), most research has focused on analysing the US political arena. It is not for nothing that YouTube was used for the first time as a political propaganda tool in the 2006 US midterm elections. In this regard, Gueorguieva (2008) performed a ground-breaking study on the influence of the video website on those elections, analysing how the candidates benefitted from its use and the challenges that it posed for media officers. Thenceforth, deeper enquiries were made into the use of the platform in successive election campaigns. For instance, the 2008 presidential elections were the object of study of Church (2010) and Robertson et al. (2010), who analysed the videos of the candidates, paying special attention to their leadership skills and the interconnection between YouTube and other social media during the election campaign, respectively. The 2010 midterm elections were studied by Vaccari and Nielsen (2013), among others, who monitored the popularity of the candidates on websites and the social media. In this respect, the authors discovered that the online popularity of the candidates did not depend on the media coverage that they received, poll results or the money spent on the campaign, for which reason the use of social media, especially Twitter and YouTube could serve to give a boost to less well-known candidates, while also possibly increasing partisan polarization.

In relation to this polarization and in connection with disinformation, Chen and Wang (2022) examined the social contagion of political incivility resulting from the campaign that Donald Trump launched on the platform during the 2020 presidential election campaign. In the same vein, Bisbee et al. (2022) have recently focused on the proliferation of theories about possible electoral fraud and conspiracies after the election results had been announced, concluding that those users who were more sceptical about the legitimacy of the elections were more prone to find content recommended by YouTube whose narratives were akin to those ideas, as well as underscoring the danger of a mechanism that seems to fuel disinformation.

Over the past few years, a considerable amount of international research has revolved around the growing concern over the possibility that SNSs, and YouTube in particular owing to its recommender system, may promote the radicalization and polarization of online audiences. In this connection, Chung and Cheng (2022) have analysed the profiles of some pro-government youtubers who have polarized and fragmented the Hong Kong media landscape, using social media data and qualitative textual analysis. Similarly, Tran et al. (2022) have proposed a way of measuring political polarization using a user-activity-based model, revealing that users are acutely polarized (in both left- and right-wing channels).

In Spain, many studies have been performed on both national (Berrocal-Gonzalo et al., 2017; Gómez & López, 2016) and regional (Vázquez, 2016, 2017; Gandlaz et al., 2020) elections. Some such studies indicate that most political communication content on YouTube is generated by the media, for which reason there is talk of the mediatization of this space, which the public sphere has traditionally occupied (Gil-Ramírez, 2019). Therefore, the level of participation of prosumers in the creation of original content for the platform is rather low (Berrocal et al., 2014; Gil-Ramírez, 2019). Furthermore, it has been noted that political parties still have not learnt how to exploit the resources and advantages of YouTube for establishing two-way communication with the citizenry or how to position themselves strategically (Gil-Ramírez and Gómez, 2020).

1.2. Political propaganda and social media in Andalusia

The study of political communication in Andalusia is interesting for two main reasons. Firstly, because of the relevant position that this autonomous community occupies in Spain, in so far as it is one of the most populated in the country (INE, 2022). Secondly, it has repeated a national pattern, namely, a two-party system led by the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and the People’s Party (Partido Popular, PP) which has given way to a multiparty or “fragmented multiparty” system (Rama, 2016). Following its creation in 1982, the PSOE Andalusia (PSOE Andalucía, PSOE-A) won absolute majorities in the Andalusian parliament until 1994, after which it began to govern in coalition with other left-wing parties. It was following the 2015 elections, with the appearance of two emerging parties, Podemos Andalusia and Cs Andalusia (Cs-A), with quite different ideological stances, that the new party system in Andalusia began to take shape. On the one hand, Podemos Andalusia, which aspired to replace the PSOE-A, obtained 14.84 per cent of the ballots cast and, on the other, the centre-right party Cs-A, 9.28 per cent. The appearance of two new parties in Andalusia reflected the transformation that the Spanish political scene had been undergoing, while also bringing the curtain down on the PSOE-A’s 36 years of hegemony.

Nevertheless, real change came about in the 2018 regional elections, when the PSOE became the main opposition party in Parliament for the first time in its history, despite having been the most voted party. So, for the first time in the history of the autonomous community, the Andalusian government was formed by a centre-right coalition between the PP of Andalusia (PP-A) and Cs-A, with the parliamentary support of the radical right-wing Vox Andalusia (Ferreira, 2019). It was the first time that the party, created by the most conservative sectors of the PP in 2013, had achieved electoral success, obtaining 10 per cent of the ballots cast and winning twelve seats in the Andalusian parliament.

This is how the advent of the Internet and social media has also transformed the way of doing politics in Andalusia, a phenomenon that has aroused the interest of researchers and scholars. For example, Carrasco-Polanco et al. (2020) analysed the use of Instagram during the 2018 election campaign, underscoring the potential of memes for disseminating content, the engagement achieved by individual journalists in comparison to news agencies and the notable use to which Vox Andalusia put this SNS, evincing the comprehensive strategic planning of its propaganda campaigns. As usually occurs in political communication practices, however, Twitter is the SNS that has monopolized the literature. In this regard, based on their study of the 2012 Andalusian elections, Deltell et al. (2013) proposed a model for predicting election trends using Twitter which, for them, is more accurate than traditional polls, since it minimizes prediction errors. For their part, Bustos and Ruiz (2016) analysed the images posted by the main political parties and their candidates running in the 2015 Andalusian elections, examining their content and effects. These authors emphasized the minimal activity of the social media profiles of the candidates, their parties playing the leading role in the election campaign. They also highlighted the predominance of images in social media campaigns (albeit questioning their quality) as a vehicle for conveying political ideas.

For their part, Pérez-Curiel and García (2019) enquired into the current system of television debates, as well as their coverage on Twitter, drawing some rather unflattering conclusions since they have ceased to awaken the interest of public opinion. With respect to this SNS, the authors specifically decried the abuse of “personalization”, which meant that the candidates took precedence over ideological and discursive aspects and the predominance of a one-way discourse, in contrast to the two-way sort supposedly facilitated by social media. Not knowing how to leverage the advantages offered by SNSs for political communication has been a frequent conclusion of the empirical studies performed to date.

In another vein, based on the manipulation of popular culture for propaganda purposes Donstrup (2020) analysed the references to the Game of Thrones and The Avengers in the (re)tweets posted on the official account of the regionalist left-wing coalition Forward Andalusia. The study’s findings pointed to the superficiality of those references and the lack of an adequate strategy when employing them in its political communication, focusing more on the productions’ popularity than on their ideological baggage.

Lastly, returning to the use to which Vox puts social media, Rivas-de-Roca et al. (2020) explored the influence of the radical right on the public debate among political leaders on Twitter, yet again analysing the specific case of the 2018 Andalusian elections. Their analysis of Vox Andalusia is in line with other studies mentioned here in the theoretical framework section, underlining its adept social media management: “The Vox candidate worked as an influencer of the digital political debate, making the far-right a central issue of the campaign despite being an extra-parliamentary” (p. 238).

1.3. Political propaganda and YouTube in Andalusia

The literature on the political use of YouTube in Andalusia is thin on the ground and, often, tends to address the issue in the broader frame of what could be called the “social media mix”. For instance, Rivero-Rodríguez (2013) examined the situation 2.0 of local Andalusian politics, focusing on how the PP-A, the PSOE-A and United Left Andalusia (Izquierda Unida Andalucía, IU-A) used Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. According to the conclusions of this author, those parties did not take full advantage of YouTube, while highlighting that the content that they posted did not usually go viral. For his part, Prieto Rodríguez (2016) performed an analysis on the level of personalization of the political campaigns launched on the three social media in Andalusia in 2012 and 2015. The results revealed that the PP-A and the PSOE-A doubled their presence on YouTube in 2012 as regards both channels (party and candidates), whereas IU-A only used its party channel. During the 2015 election campaign, the PP-A and Podemos Andalusia decided to personalize their campaigns doubling the number of channels on the platform, while the PSOE-A resorted to its official party channel.

Gil-Ramírez et al. (2020) focused on the type of political debate that was generated among the audience of YouTube videos under the label “2018 Andalusian elections” and how this contributed to reinforce the democratic system. They determined that neither the political nor the media sphere participated in the ideological debate on YouTube. In turn, Pineda et al. (2022) have conducted an analysis on the political communication of the Andalusian parties with parliamentary representation on YouTube, arriving at the conclusion that they used the platform to announce their positions or to attack rival parties and/or governments, a strategy benefitting brands (parties) more than individual leaders.

In the specific context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the main aim of the Andalusian political parties was to disseminate information and propaganda on YouTube, while disregarding interaction and dialogue with the citizenry (Pineda et al., 2022). The predominance of right-wing and, above all, radical right-wing ideology represented by Vox Andalusia, in the use of this video platform is striking. Vox Andalusia was thus the party that used it most to express its political stances, as well as to attack its rivals for propaganda purposes. Once again, this not only confirmed the results of previous studies, but also the words of the consultor Gustavo Entrala, for whom “male conservatives have turned YouTube into their stronghold: they look for videos they can’t find on traditional media sites” (Viejo and Alonso, 2018).

2. OBJECTIVES

In light of the previous literature, the main objective of this paper is to gain further insights into the political use to which the Andalusian parties put YouTube, drawing from the hypothesis that it is those parties more far removed from the centre of the ideological spectrum and, specifically, the radical right Vox Andalusia, that use the platform most effectively, leveraging it to disseminate content and propaganda, alike. Thus, specifically, the present study seeks to identify the data related to reactions and interactivity towards audiovisual messages, while simultaneously examining the type of propaganda used, whether it is directed towards any rival organization, and the personal and iconic elements of the party that are employed.

3. METHODOLOGY

A content analysis was performed on 999 videos posted on YouTube throughout 2020. This figure corresponds to the universe of videos posted by the different political parties and coalitions with seats in the Andalusian parliament following the elections held on 2 December 2018: the PSOE-A (63), the PP-A (81), Cs-A (174), Forward Andalusia (173) and Vox Andalusia (508). Nevertheless, as some of the parties initially forming part of Forward Andalusia abandoned the coalition in 2020 (Riveiro, 2020; Santaeulalia, 2020), an individual analysis of the videos posted by these parties was performed: Forward Andalusia (58), Podemos Andalusia (33), IU-A (65), Andalusian Left (Izquierda Andalucista) (1) and Anti-capitalists Andalusia (Anticapitalistas Andalucía) (16). The videos were coded between 11 January 2021 and 16 January 2022.

Apart from the formal data and those on interactivity (length, views, links, hashtags, likes and dislikes) (Cartes Barroso, 2018; Gómez and López, 2016; Graham et al., 2013; López-Rabadán and Mellado, 2019; Verón and Pallarés, 2017) the variables relating to the propaganda slant of the videos analysed were coded following Pineda (2006) and Lalancette and Raynauld (2019):

- The presence of the party’s top regional leader: (a) yes, (b) no, (c) undetermined.

- Party symbols: (a) flag, (b) logo, (c) anthem, (d) none, (e) other, (f) undetermined.

- Colour predominating in the video (corporately associated with the party): (a) red, (b) blue, (c) purple, (d) orange, (e) green (f) other, (g) without a predominant colour.

- Type of propaganda: (a) assertion, (2) denial, (3) reaction, (4) undetermined. In other words, following Pineda Cachero (2006) the idea here was to determine whether the message was aimed at extoling the party, without any reference to or representation of rivals (assertion propaganda), focused on attacking and dismissing rivals (denial propaganda) or, on the contrary, placed the accent on the negative aspects of rivals to acclaim the party’s own stance (reaction propaganda).

- Reference to a rival political party: (a) Forward Andalusia, (b) Anti-capitalists Andalusia, (c) Cs-A, (d) IU-A, (e) Andalusian Left, (f) Podemos Andalusia, (g) PP-A, (h) PSOE-A, (i) Vox Andalusia, (j) other, (k) undetermined/none.

The analysis was performed by two coders. As to the reliability of the measurement tool, after a first round of training an intercoder test was run, obtaining a Krippendorff’s (2004) α coefficient lower than expected, especially for variables relating to propaganda. So, further training was required to clarify terms and to prepare a codebook for the second set of variables. In the second test that was run, a score of 0.94 was obtained for the variables relating to data on interactivity, views, likes and comments, and one of 0.84 for the propaganda variables. The IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software package was used for the data analysis.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

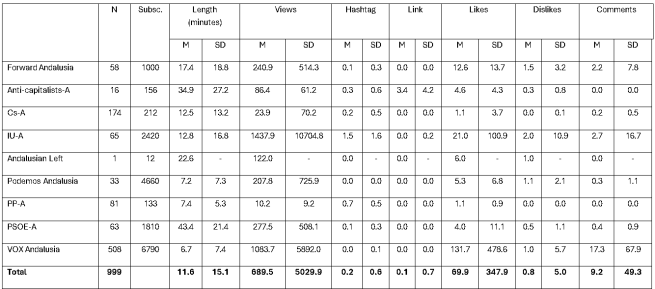

Regarding the formal data for the videos and interactivity (Table 1), the first aspect that should be highlighted was the absence of hashtags —usually employed less often on YouTube than on other social media platforms— and links associated with the videos. Likewise, there were clear differences in the average number of views, likes and, to a lesser extent, comments. Besides the fact that Vox Andalusia was the most active party on the platform, it also obtained the highest average number of views and likes, followed by IU-A. Be that as it may, these two parties also obtained the most varied results. For example, the video entitled, “¡VOX has managed to put an end to the inclusive language imposed by the Left!” obtained 110,945 views and 9,508 likes while the IU-A video “Final farewell to Julio Anguita at Cordova City Hall” received 86,410 views and 820 likes, in sharp contrast to the rest of their videos, which obtained more modest results. It seems clear that it was the parties to the right of the ideological spectrum (Vox Andalusia, PP-A and Cs-A) that were the most active on YouTube, accounting for 76.38 per cent of the video sample. As regards Andalusian Left, the party had posted only one video on its YouTube channel which, to make matters worse, only had twelve subscribers. For the reasons set out above, it was decided to include the video in the analysis, although this anomaly was considered in the subsequent analyses, given that it might have given rise to problems when evaluating the overall results.

With respect to user comments, they were very few and far between and none of them received any reply from the official channels, a fact that should be highlighted given the opportunities that the platform offers for interaction and starting conversations.

Table 1. Formal data and interactivity.

Source: Own elaboration.

Moving on to the variables relating to the presence of the regional leaders (Table 2), they only appeared or were referred to in 16.62 per cent of the videos, this being most notable in the case of IU-A (apart from Andalusian Left with only the one video), with Toni Valero, the party’s coordinator, appearing often in them. The opposite can be said of Podemos Andalusia, Vox Andalusia and Forward Andalusia, whose regional leaders’ visibility was very low or non-existent. In this matter, there were statistically significant differences in relation to the appearance of the regional leaders in the videos in terms of the political party (X2(8) = 333.691; p < 0.001).

Table 2. Presence of regional leaders and party symbols (%).

|

|

Regional leader |

Flag |

Logo |

Anthem |

Party colour |

Total |

|

Forward Andalusia |

1.72 |

0.00 |

79.31 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

58 |

|

Anti-capitalists-A |

18.75 |

0.00 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

16 |

|

Cs-A |

37.93 |

0.00 |

2.87 |

1.15 |

5.17 |

174 |

|

IU-A |

64.62 |

1.54 |

30.77 |

0.00 |

3.08 |

65 |

|

Andalusian Left |

100.00 |

0.00 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1 |

|

Podemos Andalusia |

0.00 |

0.00 |

63.64 |

0.00 |

93.94 |

33 |

|

PP-A |

44.44 |

0.00 |

97.53 |

0.00 |

1.23 |

81 |

|

PSOE-A |

25.40 |

4.76 |

92.06 |

85.71 |

1.59 |

63 |

|

VOX Andalusia |

0.20 |

1.57 |

82.68 |

0.98 |

4.92 |

508 |

|

Total |

16.62 |

1.13 |

62.48 |

5.72 |

6.91 |

999 |

Source: Own elaboration.

As to party symbols, nor were they exploited as a rule, besides the logo, which usually appeared in one of the corners as a sort of signature. Regarding flags and hymns, it was the PSOE-A that made greater use of them, above all the latter, which, together with a green placard featuring the party’s logo and the campaign slogan, was used to introduce the live broadcasting of press conferences for example, the PSOE of Andalusia (2020). In the main, however, the use to which all the parties put these two symbols was negligible: 1.13 and 5.72 per cent, respectively. Lastly, concerning the use of corporate colours, the results were also similar, for only 6.91 per cent of the videos featured them, except in the case of Podemos Andalusia, which employed purple, even if only as a background colour, in 93.94 per cent of its videos —for example, Podemos Andalucía (2020a; 2020b)—. As before, there were statistically significant differences in the use of corporate colours in terms of the party (X2(8) = 406.557; p < 0.001). Nevertheless, this finding should be linked to the fact that, in the case of Andalusia, most of the political parties tend to use green because it represents the region’s flag, incorporating it into their political events, either using it in substitution for their corporate colours, like the PSOE-A in the previous example, or integrating it, as in the second case of Podemos Andalusia. In point of fact, the two main parties, namely the PSOE-A and the PP-A used this colour in 88.89 and 69.14 per cent of their videos, respectively.

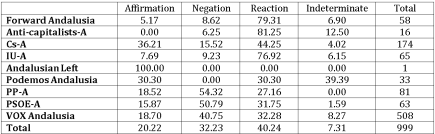

On the other hand, considering the results, the type of propaganda employed (Table 3) is even more interesting, for 72.47 per cent of the videos posted resorted to the denial or reaction sort, especially the latter. For instance, the political parties and coalitions more to the left of the ideological spectrum, including Anti-capitalists Andalusia, Forward Andalusia, IU-A and, in a lower degree, Podemos Andalusia, conveyed messages that could be classified as reaction propaganda, contrasting their proposals (or directly their values and organizations) with those of their rivals. Whereas although the PSOE-A, the PP-A and Vox Andalusia also employed this type of propaganda, they resorted more to the denial kind, attacking, and dismissing their rivals, without clarifying their own position vis-à-vis burning issues. An example of reaction propaganda can be found in the video posted by Forward Andalusia (Adelante Andalucía, 2020) in which Teresa Rodríguez, the party’s leader, contrasts her decision to forego parliamentary travel allowances owing to the mobility restrictions in place following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, with that of the rest of the parties whose members of parliament had chosen to continue to claim them. As to denial propaganda, for its part, a good example is the video entitled, “VOX Andalusian Parliament” (2020), decrying the incompetence of the coalition government, formed by the PP-A and Cs-A, without putting forward any alternatives, taking any stance or even explicitly substantiating such a claim. When crossing the variables, there were statistically significant differences (X2(24) = 247,517; p < 0.001) in the way in which each political party employed this type of propaganda.

Table 3. Type of propaganda employed (%).

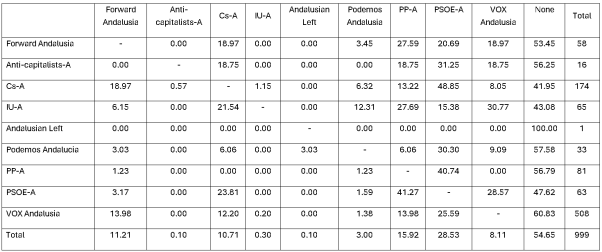

To end with, in relation to references to rival parties (Table 4), albeit absent in over half of the video sample (54.65%), most had to do with the PSOE-A (28.53%) —which was currently governing the county in coalition with Unidas Podemos—, PP-A (15.92%) —governing the region with Cs-A at the time— or both (7.31%), which can be understood as an attack against the government as a whole or even against the traditional two-party system. As to the main reference in each one of the videos, it can be observed how, within that two-party logic and the confrontation between territorial powers, the two aforementioned parties tended to target each other. Likewise, broadly speaking, the parties to the left of the ideological spectrum, like Forward Andalusia, Anti-capitalists Andalusia and Podemos Andalusia usually referred, in a different order of precedence, to the PSOE-A, the PP-A and Vox Andalusia, whereas this last party mostly referred to the PSOE-A, as well as to the PP-A and Forward Andalusia to roughly the same degree.

Table 4. References to rival parties (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

The advent of the Internet and social media has modified the communication strategies of political parties and leaders. In this regard, these new tools/channels have facilitated the development of a more intense and wide-reaching propaganda, placing the accent on the personalization and privatization of messages, plus the idea of permanent campaigning (Castells, 2009; Maarek, 2011; McGregor et al., 2017; Rivero-Rodríguez, 2013). Nonetheless, these new forms of propaganda are no more than revamped versions of the traditional kind, far removed from the opportunities for two-way communication and conversation between the citizenry and political representatives that these social media were expected to offer (Gil-Ramírez and Gómez de Travesedo-Rojas, 2020; Larsson and Moe, 2011; Pérez-Curiel and García, 2019; Ramos-Serrano et al., 2018); a point that has also been corroborated in this study focusing on Andalusia. So, even though YouTube does not stand out especially for the opportunities for dialogue that it offers, in contrast to Twitter, Facebook and even Instagram, it is no less striking that none of the users commenting on the videos received a reply from the official channels on which they were posted.

Another notable aspect was the low number of user comments in general, with the exception of Vox Andalusia, which was also the party posting the largest number of videos, with the shortest average length, on its official channel during the study time frame, in line with the findings of the study performed by Gil-Ramírez et al. (2020). This would confirm the starting hypothesis according to which Vox Andalusia put social media to the most effective use (Cervi and Marín-Lladó, 2021; Cid, 2020; Simón, 2020). This last aspect is relevant because, although the average length of the videos posted by other parties like Podemos Andalusia and the PP-A was also below eight minutes, that of the videos of the PSOE-A and Anti-capitalists Andalusia was over half an hour, which calls into question their possible effectiveness. In this connection, beyond the idea that it is easier to position longer videos among the most viewed (Simon, 2019), it is recommended that, if they are not too dull, they should last less than eight minutes (Miley, 2022). Similarly, nor was there a lavish use of hashtags, thus making the videos more difficult to find (Bagadiya, 2022).

As regards the presence of the regional leaders and party symbols, firstly it is important underscore the lack of prominence of the former, except in the case of IU-A, the PP-A and Cs-A, which would be in opposition to the idea of the growing personalization and individualization of politics. This contradicts the findings of some of the studies mentioned above, such as those performed by Vaccari and Nielsen (2013), Prieto Rodríguez (2016) and Sánchez-Labella (2020), while being more in line with the conclusions of research like that conducted by Bustos and Ruiz (2016). It is, however, important to take into consideration that the analysis has focused here on the official channels of the political parties, on which they would be expected to attach greater importance to their organizations as a whole. Nevertheless, this last aspect should be contrasted with the absence of symbols representing the different political parties, including flags, hymns and corporate colours, which were rarely employed, except in the case of the logo and hymn of the PSOE-A and the corporate colour of Podemos Andalusia. But this was limited even in these two cases, with the hymn of the PSOE-A being used in combination with a placard indicating that the “live broadcast” had not yet begun (thus prompting users to skip it when viewing the videos on demand) and in that of the corporate colour (purple) of Podemos Andalusia, which was only used in the background and, moreover, too indistinct to be fully appreciated. The use of green, the colour representing Andalusia, was indeed more widespread, which meant that it was often difficult to differentiate between the region’s political parties, while also calling into question the findings of other similar studies, like that performed by Bustos and Ruiz (2016).

With respect to the type of propaganda, the clearest difference was between the video messages of the PP-A, the PSOE-A and, to a lesser extent, Vox Andalusia, and those of Anti-capitalists Andalusia, Forward Andalusia, and IU-A. The former preferred denial propaganda, criticizing and decrying the policies and actions of their rivals, but without offering any alternatives, while the latter did indeed contrast these opposing stances with their own (Pineda et al., 2022). In this sense, there is a clear distinction inasmuch as positive propaganda, the sending party in this case, is explicitly expressed in reaction propaganda and only implicitly in the denial kind, for after all the party conveying the message always seeks to obtain a benefit (Pineda, 2006).

5. CONCLUSIONS

The main conclusion drawn from this study is that, generally, Andalusian political parties barely harness the potential of the YouTube platform, neither in terms of leveraging visual elements nor, indeed, in terms of interactivity. The findings suggest a missed opportunity for political parties in Andalusia to effectively utilize YouTube for disseminating content, engaging the audience, and fostering a more dynamic and participatory online presence. Beyond this, the political parties’ failure to put forward alternatives is framed in the broader context of a pseudo abandonment of ideology and the rise of populism in politics, which has been traditionally associated with a reduction in the number of programmatic ideas. So small wonder that it was Vox Andalusia, as noted in previous studies, that leveraged YouTube most, with a much greater presence on the platform than the rest of the parties and the official channel with the highest number of subscribers and likes, although the latter had more to do with the posting of especially viral videos. From the perspective of personalization, the use of symbols or even the type of propaganda employed, however, it was not a party that really stood out, at least in the Andalusian political context. Therefore, the starting hypothesis, to wit, that the radical right-wing Vox Andalusia was the party that used the platform most for disseminating content and propaganda, would be partially refuted. On the contrary, parties to the left of the ideological spectrum, like Anti-capitalists Andalusia and IU-A, stood out particularly for their use of reaction propaganda, although it warrants recalling that they posted much fewer videos.

Lastly, in relation to references to other parties, the PSOE-A and the PP-A continued to be the two main rivals, for it is with good reason that they are currently governing at a national and regional level, respectively. Nonetheless, it is remarkable how IU-A focused its attacks on Vox Andalusia (as well as on the PP-A), attaching the same importance to this party as to the PSOE-A. Just as the radical right-wing party had voted in favour of the swearing in of Juanma Moreno of the PP-A as the president, so too did Cs-A, with which the PP-A formed a coalition government, but, nonetheless, was the target of less criticism. At present, following the Andalusian elections held on 19 June 2022, it is impossible to ignore that Vox Andalusia now has 14 seats and Cs-A none. The new makeup of the regional government implies a change in the variables on which this study is based and, by and large, has given rise to a different scenario to which the same methodology could be applied with a view to performing a comparative analysis between the previous and current situation. In addition to a diachronic study of the use of YouTube by the Andalusian political parties with parliamentary representation, other future lines of research could include autonomous communities whose governments have a similar or different makeup, thus resulting in a nationwide comparative analysis. For the same reason, the results obtained could be supplemented by a qualitative discourse analysis of some of the most relevant videos, considering that several specific examples evincing that extremism were detected.

On the other hand, from an instrumental perspective, the results presented here have a potential professional application since they could be of use to those responsible for the political communication of the Andalusian parties and their leaders. In this regard, a series of recommendations could be made for the purpose of helping political parties to use this platform more effectively in Andalusia (and, by extension, in the rest of the country), making the most of the opportunities that it offers, above all in relation to its two-way and interactive nature.

6. REFERENCES

Adelante Andalucía. (2020, April 20). Nosotras cumplimos. Hemos devuelto las dietas y donado parte de nuestro sueldo [Video]. YouTube. https://tinyurl.com/48mw7vvd

Armstrong, J. y Moulitsas, M. (2006). Crashing the gate. Netroots, grassroots, and the rise of people-powered politics. Chelsea Green.

Bagadiya, J. (2022). How to tag YouTube videos for increasing your channel views. SocialPilot. https://tinyurl.com/226ztksh

Balci, Ş. y Saritaş, H. (2022). Political communication on social media: The analysis of YouTube advertisements for March 31, 2019 local elections. Turkish Review of Communication Studies, 40, 239-256. https://doi.org/10.17829/turcom.930855

Berrocal Gonzalo, S., Campos Domínguez, E. y Redondo García, M. (2014). Prosumidores mediáticos en la comunicación política, el ‘politainment’ en YouTube. Comunicar, 43(22), 65-72. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-06

Berrocal-Gonzalo, S., Martín-Jiménez, V. y Gil-Torres, A. (2017). Líderes políticos en YouTube: Información y politainment en las elecciones generales de 2016 (26J) en España. Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 937-946. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.15

Bisbee, J., Brown, M., Lai, A., Bonneau, R., Nagler, J. y Tucker, J. A. (2022). Election fraud, YouTube, and public perception of the legitimacy of President Biden. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v1i3.60

Bustos Díaz, J. y Ruiz Del Olmo, F. J. (2016). La imagen en Twitter como nuevo eje de la comunicación política. Opción, 32(7), 271-290.

Carrasco-Polanco, R., Sánchez-de-la-Nieta-Hernández, M. Á. y Trelles-Villanueva, A. (2020). Las elecciones al parlamento andaluz de 2018 en Instagram: partidos políticos, periodismo profesional y memes. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 11(1), 75-85. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2020.11.1.19

Cartes Barroso, M. J. (2018). El uso de Instagram por los partidos políticos catalanes durante el referéndum del 1-O. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 47, 17-36. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2018.0.17-36

Castells, M. (2009). Communication Power. OUP.

Cervi, L. y Marín-Lladó, C. (2021). What are political parties doing on TikTok? The Spanish case. Profesional de la Información, 30(4). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.jul.03

Chaudhari, D. D. y Pawar, A. V. (2021). Propaganda analysis in social media: A bibliometric review. Information, Discovery and Delivery, 41(1), 57-70. https://doi.org/10.1108/IDD-06-2020-0065

Chen, Y. y Wang, L. (2022). Misleading political advertising fuels incivility online: A social network analysis of 2020 U.S. presidential election campaign video comments on YouTube. Computers in Human Behavior, 131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107202

Chomsky, N. y Herman, E.S. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon Books.

Chung, H. y Cheng, E.W. (2022). Constructing patriotic networked publics: conservative YouTube influencers in Hong Kong. Chinese Journal of Communication, 15(3), 415-430. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2022.2093238

Church, S. C. (2010). YouTube politics: YouChoose and leadership rhetoric during the 2008 election. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 7(2-3), 124-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681003748933

Cid, G. (2020, June 24). “Baja un dedo si eres de derechas”. La oscura guerra política que viven tus hijos en TikTok. El Confidencial. https://tinyurl.com/keatnww9

Davis, R., Baumgartner, J. C., Francia, P. L. y Morris, J. S. (2009). The Internet in U.S. election campaigns. In A. Chadwick, & P. N. Howard (Eds.). Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics (pp. 13-24). Routledge.

Deltell, L., Claes, F. y Osteso, J. M. (2013). Predicción de tendencia política por Twitter: Elecciones Andaluzas 2012. Ámbitos, 22, 1-16.

Donstrup, M. (2020). Intersecciones entre la cultura de masas y la propaganda: El cine y la televisión en la estrategia política de Adelante Andalucía. Oceánide, 12, 54-62. https://doi.org/10.37668/oceanide.v12i.25

Ferreira, C. (2019). Vox como representante de la derecha radical en España: un estudio sobre su ideología. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 51, 73-98. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.51.03

Finlayson, A. (2020). YouTube and political ideologies: Technology, populism and rhetorical form. Political Studies, 70(1), 62-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720934630

Fischer, T., Kolo, C. y Mothes, C. (2022). Political influencers on YouTube: Business strategies and content characteristics. Media and Communication, 10(1), 259-271. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4767

Gandlaz, M., Larrondo Ureta, A. y Orbegozo Terradillos, J. (2020). Viralidad y engagement en los spots electorales a través de YouTube: el caso de las elecciones autonómicas vascas de 2016. Mediatika, 18, 177-206.

Gil-Ramírez, M. y Gómez de Travesedo-Rojas, R. (2020). Management of Spanish politics on YouTube. A pending issue. Observatorio, 14(1), 22-44. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS14120201491

Gil-Ramírez, M. (2019). El uso de YouTube en el Procés Catalán. Comunicación política a través de los social media: ¿prosumidores mediatizados? Estudio sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 25(1), 213-234. https://doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.63725

Gil-Ramírez, M., Gómez-de-Travesedo-Rojas, R. y Almansa-Martínez, A. (2020). Political debate on YouTube: revitalization or degradation of democratic deliberation? Profesional de la Información, 29(6). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.38

Gómez de Travesedo, R. y López, P. (2016). La utilización de YouTube por parte de los principales partidos políticos durante la precampaña de 2015 en España. In C. Mateos Martín, & F. J. Herrero Gutiérrez (Eds.). La pantalla insomne (pp. 3120-3136). SLCS.

Graham, T., Broersma, M., Hazelhoff, K. y van ‘t Haar, G. (2013). Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters. Information, Communication & Society, 16(3), 692-716. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.785581

Gueorguieva, V. (2008). Voters, MySpace, and YouTube. Social Science Computer Review, 26(3), 288-300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439307305636

INE. (2022). Official population figures referring to revision of municipal register 1 January. Population by Autonomous Communities. INE. https://tinyurl.com/mhan8muf

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis. SAGE.

Lalancette, M. y Raynauld, V. (2019). The power of political image: Justin Trudeau, Instagram, and Celebrity Politics. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(7), 888-924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217744838

Lima-Lopes, R. E. (2022). Our saviour will not be a woman: Users’ political comments on YouTube talk show official channel. Alfa, 66, 1-36. https://acortar.link/v2DP77

Larsson, A. O. y Moe, H. (2011). Studying political microblogging: Twitter users in the 2010 Swedish election campaign. New Media & Society, 14(5), 729-747. htpps://doi.org/ 10.1177/1461444811422894

Litvinenko, A. (2021). YouTube as alternative television in Russia: Political videos during the presidential election campaign 2018. Social Media + Society, 7(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984455

López-Rabadán, P. y Mellado, C. (2019). Twitter as a space for interaction in political journalism, dynamics, consequences and proposal of interactivity scale for social media. Communication and Society, 32(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.32.37810

Maarek, P. J. (2011). Campaign Communication & Political Marketing. Wiley-Blackwell.

McGregor, S. C., Lawrence, R. G. y Cardona, A. (2017). Personalization, gender, and social media: Gubernatorial candidates’ social media strategies. Information, Communication & Society, 20(2), 264-283.

Miley, M. (2022). How long should a YouTube video be? Brafton. https://tinyurl.com/4rv3van7

Möller, A., Marthe, M. A., Kühne, R., Baumgartner, S. E. y Peter, J. (2019). Exploring user response to entertainment and political videos: An automated content analysis of YouTube. Social Science Computer Review, 37(4), 510-528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318779336

Munger, K. y Phillips, J. (2020). Right-wing YouTube: A supply and demand perspective. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(1), 186-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220964767

Pedersen, H. H. y Rahat, G. (2019). Political personalization and personalized politics within and beyond the behavioural arena. Party Politics, 27(2), 211-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819855712

Pérez-Curiel, C. y García Gordillo, M. (2019). Formato televisivo y proyección en Twitter de las elecciones en Andalucía. In E. Conde-Vázquez, J. Fontenla-Pedreira, & J. Rúas-Araújo (Eds.). Debates electorales televisados: del antes al después (pp. 257-282). SLCS.

Pineda Cachero, A. (2006). Elementos para una teoría comunicacional de la propaganda. Alfar.

Pineda, A., Hernández-Santaolalla, V., Algaba, C. y Barragán-Romero, A. (2019). The politics of think tanks in social media: FAES, YouTube and free-market ideology. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 15(1), 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.15.1.3_1

Pineda, A., Hernández-Santaolalla, V., Barragán-Romero, A. y Bellido, Elena (2022). Information, state of alert and propaganda in Spain. In T. Chari, & M. N. Ndiela (Eds.). Global Pandemics and Media Ethics. Issues and Perspectives (pp. 208-228). Routledge.

Pineda, A., Rebollo-Bueno, S. y Oliveira, J. S. (2022). The use of YouTube by political parties in Andalusia. Centra. Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 29-50. https://doi.org/10.54790/rccs.13

Podemos Andalucía. (2020a, January 21). Feminismo o barbarie. [Video] YouTube. https://tinyurl.com/3y73p9ks

Podemos Andalucía (2020b, January 21). Feminismo o barbarie. [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EHy0HJe8eyQ

Prieto Rodríguez, A. (2016). Elecciones autonómicas andaluzas 2012-2015: personalización en las campañas electorales en internet. CCCSS. https://tinyurl.com/yv8wpjkc

PSOE de Andalucía (2020, September 1). DIRECTO | Rueda de prensa de Beatriz Rubiño. [Video] YouTube. https://tinyurl.com/2vewuk2u

Rama, J. (2016). Crisis económica y sistemas de partidos. Síntomas de cambio político. Institut de Ciéncies Politique i Socials, 344, 1-29. https://tinyurl.com/4rfayr3f

Ramos-Serrano, M., Fernández Gómez, J. D. y Pineda, A. (2018). Follow the closing of the campaign on streaming: The use of Twitter by Spanish political parties during the 2014 European elections. New Media & Society, 20(1), 122-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816660730

Rivas-de-Roca, R., García-Gordillo, M. y Bezunartea-Valencia, O. (2020). The far-right’s influence on Twitter during the 2018 Andalusian elections. Communication & Society, 33(2), 227-242. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.33.2.227-242

Riveiro, A. (2020). Anticapitalistas certifica su salida de Podemos y busca redefinirse para el mundo después de la pandemia. eldiario.es. https://tinyurl.com/4nd6fa3w

Rivero-Rodríguez, A. (2013). Redes sociales en la campaña política permanente andaluza. In S. Giménez Rodríguez, & G. Tardivo (Eds.). Proyectos sociales, creativos y sostenibles (pp. 742-745). ACMS.

Robertson, S. P., Vatrapu, R. K. y Medina, R. (2010). Online video “friends” social networking. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 7(2-3), 182-201. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681003753420

Sánchez-Labella Martín, I. (2020). The use and management of public information in social media: A case study of town and city councils throughout Andalusia on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. In V. Hernández-Santaolalla, & M. Barrientos-Bueno (Eds.). Handbook of Research on Transmedia Storytelling, Audience Engagement, and Business Strategies (pp. 321-336). IGI Global.

Santaeulalia, I. (2020). Anticapitalistas abandona Podemos. El País. https://tinyurl.com/6bsz8f58

Simón, A. I. (2020). TikTok está lleno de fans adolescentes de VOX. VICE. https://tinyurl.com/yrd5wxy9

Simon, J. (2019). How to make a YouTube video. TechSmith. https://tinyurl.com/yvppun5u

Tran, G. T. C., Nguyen, L. V., Jung, J. J. y Han, J. (2022). Understanding political polarization based on user activity. SAGE Open, 12(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221094587

Vaccari, C. y Nielsen, R. K. (2013). What drives politicians’ online popularity? An analysis of the 2010 U.S. midterm elections. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 10(2), 208-222. http://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2012.758072

Vázquez Sande, P. (2016). Storytelling personal en política a través de YouTube. Comunicación y Hombre, 12, 41-55.

Vázquez Sande, P. (2017). Personalización de la política. Storytelling y valores transmitidos. Comunication & Society, 30(3), 275-291. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.30.3.275-291

Verón Lassa, J. J. y Pallarés Navarro, S. (2017). La imagen del político como estrategia electoral: el caso de Albert Rivera en Instagram. Mediatika, 16, 195-217.

Viejo, M. y Alonso, A. (2018). How Spain’s far-right Vox created a winning social media strategy. El País. https://tinyurl.com/2sfk76y4

Vijay, D. y Gekker, A. (2021). Playing politics: How Sabarimala played out on TikTok. American Behavior Scientist, 65(5), 712-734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221989769

VOX Parlamento de Andalucía. (2020, May 12). Alejandro Hernández: “La Junta está siendo incapaz de defender los intereses de Andalucía”. [Video] YouTube. https://tinyurl.com/tyeabptr

Woolley, Samuel C. y Howard, Philip N. (Eds.) (2019). Computational Propaganda. OUP.

YouTube. (2022). YouTube Official Blog. https://tinyurl.com/mravmhmb

CONTRIBUTIONS OF AUTHORS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conceptualization: Hernández-Santaolalla, Víctor; Rubio-Hernández, María del Mar y Fernández Gómez, Jorge David. Methodology and reliability: Hernández-Santaolalla, Víctor. Coding: de Oliveira, Julieti Sussi. Statistical Analysis: Hernández-Santaolalla, Víctor. Results and Discussion: Hernández-Santaolalla, Víctor; Rubio-Hernández, María del Mar y Fernández Gómez, Jorge David. Writing-Review and Editing: Hernández-Santaolalla, Víctor; Rubio-Hernández, María del Mar; Fernández Gómez, Jorge David y de Oliveira, Julieti Sussi. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This paper originates in the research project proposal PRY095/19, funded by Fundación Pública Andaluza Centro de Estudios Andaluces, 11th edition. The research project title is “Comunicación, participación y diálogo con el ciudadano en la era de la ‘nueva política’: el uso de las redes sociales por los partidos políticos en Andalucía (Communication, Participation and Dialogue with the Citizen in the Era of “New Politics”: The Use of Social Media by Political Parties in Andalusia).

Conflict of interest: The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

AUTHORS

Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla

Universidad de Sevilla.

Víctor Hernández-Santaolalla is Associate Professor of the Audiovisual Communication and Advertising Department of the Universidad de Sevilla (Spain). He holds a PhD (obtaining the Outstanding Doctorate Award) in Communication Studies. His research interests focus on the effects of mass communication, political communication, propaganda, ideology and popular culture, surveillance and social media, and the analysis of advertising discourse. He is the principal investigator of the LIGAINCOM research group (SEJ694). He has published papers in in publishing houses such as Emerald, Routledge or Peter Lang, and international journals like Information, Communication and Society, Journal of Popular Culture, Sexuality & Culture, Surveillance & Society or European Journal of Communication, among others. Recently, he has published a book on the effects of mass media, and has edited another on transmedia storytelling, audience engagement, and business strategies.

Índice H: 15

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2207-4014

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=56764642500

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Victor-Hernandez-Santaolalla

Academia.edu: https://us.academia.edu/VictorHernandezSantaolalla

María del Mar Rubio-Hernández

Universidad de Sevilla.

María del Mar Rubio-Hernández holds a PhD in Communication Studies from the Universidad de Sevilla (obtaining the Outstanding Doctorate Award), where she also earned an Advertising and Public Relations degree in 2007. She has visited foreign universities, such as the Erasmushoge School in Brussels and The University of Michigan, where she developed a special interest in the analysis of the advertising discourse. Her scientific activity focuses on collaborations with international communication magazines and conferences; moreover, she has also participated in several collective books about popular TV shows and has also co-edited two books in 2019: one about cultural branding and another about narratives genres in advertising. She combines said research work with teaching at the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising at the Universidad de Sevilla since 2011.

Índice H: 8

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8402-8067

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57189263752

Academia.edu: https://us.academia.edu/MaríadelMarRubioHernández

Jorge David Fernández Gómez

Universidad de Sevilla.

Jorge David Fernández Gómez holds a PhD (obtaining the Outstanding Doctorate Award) in Brand Management, is a lecturer in Communication at Universidad de Sevilla, Spain, and he has been a member of Department of Business Economics in the UCA. He collaborates with different universities such as Bryant University (USA) or Nova (Portugal). He has published thirteen books (McGraw-Hill, Hachette Livre, etc.) and papers in European and American scholarly journals such as New Media and Society. His research interests include brand management, popular culture, advertising strategy and advertising structure. He has worked in advertising for clients like Google, Microsoft, Bankia, P&G, Tio Pepe, or Telefonica.

Índice H: 15

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0833-6639

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57200297537

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jorge-Gomez-84

Julieti Sussi de Oliveira

Universidad de Sevilla.

Julieti Sussi de Oliveira holds a PhD in Communication with Cum Laude qualification from the Universidad de Sevilla, and with International Mention by the University of Algarve (Portugal). She is currently lecturer in the Department of Journalism II at the University of Seville. Member of the Research Group on Structure, History and Contents of Communication (GREHCCO, HUM-618), she is the Secretary of the Laboratory of Communication Studies and Editor in Portuguese of Ámbitos. International Journal of Communication. She has authored more than 40 publications on political communication, culture and power.

Índice H: 3

Orcid ID: https://doi.org/0000-0003-4476-7791